|

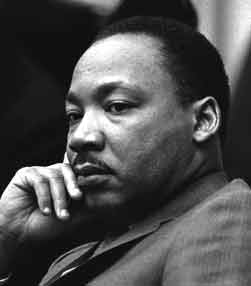

Martin Luther King, Jr.

It is a testament to the greatness of Martin Luther King Jr. that nearly every major city in the U.S. has a street or school named after him. It is a measure of how sorely his achievements are misunderstood that most of them are located in black neighborhoods. Three decades after King

was gunned down on a motel balcony in Memphis, Tenn., he is still regarded

mainly as the black leader of a movement for black equality. That assessment,

while accurate, is far too restrictive. For all King did to free blacks

from the yoke of segregation, whites may owe him the greatest debt, for

liberating them from the burden of America's centuries-old hypocrisy about

race. It is only because of King and the movement that he led that the

U.S. can claim to be the leader of the "free world" without inviting smirks

of disdain and disbelief. Had he and the blacks and whites who marched

beside him failed, vast regions of the U.S. would have remained morally

indistinguishable from South Africa under apartheid, with terrible consequences

for America's standing among nations. How could America have convincingly

inveighed against the Iron Curtain while an equally oppressive Cotton Curtain

remained draped across the South?

The movement that King led

swept all that away. Its victory was so complete that even though those

outrages took place within the living memory of the baby boomers, they

seem like ancient history. And though this revolution was the product of

two centuries of agitation by thousands upon thousands of courageous men

and women, King was its culmination. It is impossible to think of the movement

unfolding as it did without him at its helm. He was, as the cliche has

it, the right man at the right time.

Moreover, King was a man of extraordinary physical courage whose belief in nonviolence never swerved. From the time he assumed leadership of the Montgomery, Ala., bus boycott in 1955 to his murder 13 years later, he faced hundreds of death threats. His home in Montgomery was bombed, with his wife and young children inside. He was hounded by J. Edgar Hoover's FBI, which bugged his telephone and hotel rooms, circulated salacious gossip about him and even tried to force him into committing suicide after he won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964. As King told the story, the defining moment of his life came during the early days of the bus boycott. A threatening telephone call at midnight alarmed him: "Nigger, we are tired of you and your mess now. And if you aren't out of this town in three days, we're going to blow your brains out and blow up your house." Shaken, King went to the kitchen to pray. "I could hear an inner voice saying to me, 'Martin Luther, stand up for righteousness. Stand up for justice. Stand up for truth. And lo I will be with you, even until the end of the world.'" In recent years, however,

King's most quoted line—"I have a dream that my four little children will

one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of

their skin but by the content of their character"—has been put to uses

he would never have endorsed. It has become the slogan for opponents of

affirmative action like California's Ward Connerly, who insist, incredibly,

that had King lived he would have been marching alongside them. Connerly

even chose King's birthday last year to announce the creation of his nationwide

crusade against "racial preferences."

TIME national correspondent

Jack E. White has covered civil rights issues for 30 years

This article is from the "Leaders and Revolutionaries" section of the Time 100 issue in which the magazine nominated the most important 100 people of the 20th century. Copyright © 2003 Time Inc. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part without permission is prohibited. |