Select materials

by and about

Martin Luther King, Jr.

- MLK:

His place in the history of the modern civil

rights movement (1)

- MLK:

His place in the history of the modern civil

rights movement (2)

- MLK

and the Montgomery Bus Boycott

- Montogomery

Bus Boycott

- The

March on Washington "I have a Dream" Speech

- MLK:

Philosophy and Strategy of Nonviolent Resistance

- MLK:

Visit to India

- Martin

Luther King, Jr. Papers Project

- Martin

Luther King, Jr., National Historic Site's Online

Visitor Information Center

- Book:Stride Toward

Freedom: The Montgomery Story. New

York: Harper & Row, 1958.

- Book: Where Do

We Go from Here: Chaos or Community? Boston:

Beacon Press, 1968.

- Book: Baldwin,

Lewis V. Toward the Beloved Community: Martin

Luther King, Jr. and South Africa. Cleveland:

Pilgrim Press, 1995.

|

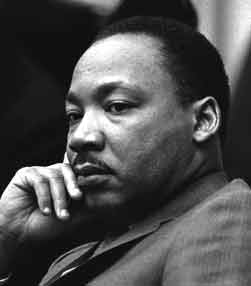

Martin Luther

King, Jr.

(15 January

1929-4 April 1968)

Martin

Luther King, Jr., made history, but he was also

transformed by his deep family roots in the

African-American Baptist church, his formative

experiences in his hometown of Atlanta, his

theological studies, his varied models of religious

and political leadership, and his extensive network

of contacts in the peace and social justice

movements of his time. Although King was only

thirty-nine at the time of his death, his life was

remarkable for the ways it reflected and inspired so

many of the twentieth century’s major intellectual,

cultural, and political developments.

The son, grandson, and great-grandson of Baptist

ministers, Martin Luther King Jr., named Michael

King at birth, was born in Atlanta and

spent his first twelve years in the Auburn Avenue

home that his parents, the Reverend Michael King and

Alberta Williams King, shared with his maternal

grandparents, the Reverend Adam Daniel (A. D.)

Williams and Jeannie Celeste Williams. After Rev.

Williams’ death in 1931, his son-in-law became

Ebenezer Baptist Church’s new pastor and gradually

established himself as a major figure in state and

national Baptist groups. The elder King began

referring to himself (and later to his son) as

Martin Luther King.

King’s formative experiences not only immersed him

in the affairs of Ebenezer but also introduced him

to the African-American social gospel tradition

exemplified by his father and grandfather, both of

whom were leaders of the Atlanta branch of the

National Association for the Advancement of Colored

People (NAACP).

Depression-era breadlines heightened King’s

awareness of economic inequities, and his father’s

leadership of campaigns against racial

discrimination in voting and teachers’ salaries

provided a model for the younger King’s own

politically engaged ministry. He resisted religious

emotionalism and as a teenager questioned some

facets of Baptist doctrine, such as the bodily

resurrection of Jesus.

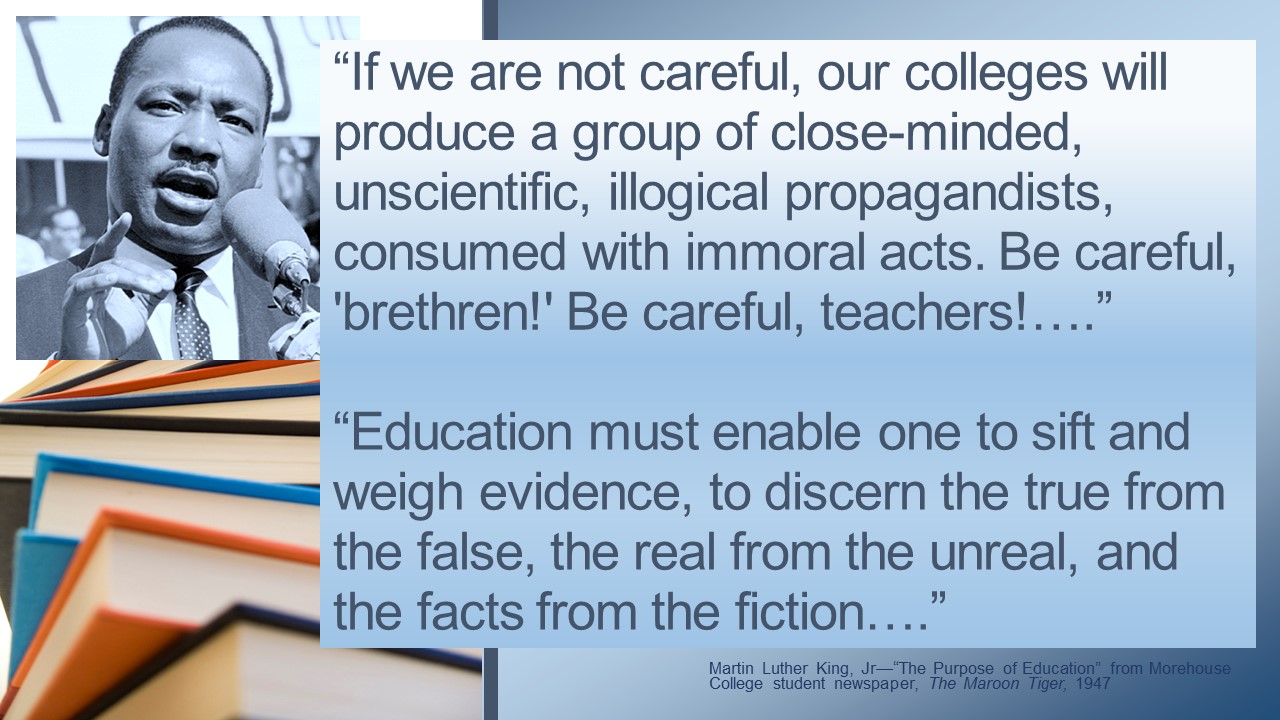

During his undergraduate years at Atlanta’s

Morehouse College from 1944 to 1948, King gradually

overcame his initial reluctance to accept his

inherited calling. Morehouse president Benjamin E.

Mays influenced King’s spiritual development,

encouraging him to view Christianity as a potential

force for progressive social change. Religion

professor George Kelsey exposed him to biblical

criticism and, according to King’s autobiographical sketch,

taught him “that behind the legends and myths of the

Book were many profound truths which one could not

escape” (Papers 1:43). King admired both educators

as deeply religious yet also learned men and by the

end of his junior year, such academic role models

and the example of his father led King to enter the

ministry. He described his decision as a response to

an “inner urge” calling him to “serve humanity”

(Papers 1:363). He was ordained during his final

semester at Morehouse, and by this time King had

also taken his first steps toward political

activism. He had responded to the postwar wave of

anti-black violence by proclaiming in a letter to

the editor of the Atlanta Constitution that African

Americans were “entitled to the basic rights and

opportunities of American citizens” (Papers

1:121). During his senior year King joined the

Intercollegiate Council, an interracial student

discussion group that met monthly at Atlanta’s Emory

University.

MLK with President Lyndon B.

Johnson

After

leaving Morehouse, King increased his understanding

of liberal Christian thought while attending Crozer

Theological Seminary in Pennsylvania from 1948 to

1951. Initially uncritical of liberal theology, he

gradually moved toward Reinhold Niebuhr’s

neoorthodoxy, which emphasized the intractability of

social evil. Mentored by local minister, J. Pius

Barbour, he reacted skeptically to a presentation on

pacifism by Fellowship of Reconciliation leader A.

J. Muste. Moreover, by the end of his seminary

studies King had become increasingly dissatisfied

with the abstract conceptions of God held by some

modern theologians and identified himself instead

with the theologians who affirmed personalism, or a

belief in the personality of God. Even as he

continued to question and modify his own religious

beliefs, he complied an outstanding academic record

and graduated at the top of his class.

In 1951 King began doctoral studies in systematic

theology at Boston University’s School of Theology,

which was dominated by personalist theologians such

as Edgar Brightman and L. Harold DeWolf. The papers

(including his dissertation) that King wrote during

his years at Boston displayed little originality,

and some contained extensive plagiarism; but his

readings enabled him to formulate an eclectic yet

coherent theological perspective. By the time he

completed his doctoral studies in 1955, King had

refined his exceptional ability to draw upon a wide

range of theological and philosophical texts to

express his views with force and precision. His

ability to infuse his oratory with borrowed

theological insights became evident in his expanding

preaching activities in Boston-area-churches and at

Ebenezer, where he assisted his father during school

vacations.

During his stay in Boston, King also met and courted

Coretta

Scott, an Alabama-born Antioch College

graduate who was then a student at the New England

Conservatory of Music. On 18 June 1953 the two

students were married in Marion, Alabama, where

Scott’s family lived.

Although he considered pursuing an academic career,

King decided in 1954 to accept an offer to become

the pastor of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in

Montgomery, Alabama. In December 1955, when

Montgomery black leaders, such as Jo Ann Robinson,

E. D. Nixon, and Ralph Abernathy formed the

Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) to protest

the arrest of NAACP official Rosa

Parks for refusing to give up her bus seat to

a white man, they selected King to head the new

group. In his role as the primary spokesman of the

year-long Montgomery

bus boycott, King utilized the leadership

abilities he had gained from his religious

background and academic training to forge a

distinctive protest strategy that involved the

mobilization of black churches and skillful appeals

for white support. With the encouragement of Bayard

Rustin, Glenn Smiley, William Stuart Nelson and

other veteran pacifists, King also became a firm

advocate of Mohandas

[Mahatma] Gandhi’s precepts of nonviolence,

which he combined with Christian social gospel

ideas.

After the United States Supreme Court

outlawed Alabama bus segregation laws in Browder v.

Gayle in late 1956, King sought to expand the

nonviolent civil rights movement throughout the

South. In 1957 he joined with C. K. Steele, Fred

Shuttlesworth and T .J. Jemison in founding the

Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC)

with King as president to coordinate civil rights

activities throughout the region. Publication of

Stride Toward Freedom: The Montgomery Story (1958)

further contributed to King’s rapid emergence as a

national civil rights leader. Even as he expanded

his influence, however, King acted cautiously.

Rather than immediately seeking to stimulate mass

desegregation protests in the South, King stressed

the goal of achieving black voting rights when he

addressed an audience at the 1957 Prayer Pilgrimage

for Freedom.

King’s rise to fame was not without personal

consequences. In 1958 King was the victim of his

first assassination attempt. Although his house had

been bombed several times during the Montgomery bus

boycott, it was while signing copies of Stride

Toward Freedom that Izola Ware Curry stabbed him

with a letter opener. Surgery to remove it was

successful, but King had to recuperate for several

months, giving up all protest activity.

One of the key aspects of King’s leadership was his

ability to establish support from many types of

organizations including labor unions, peace

organizations, southern reform organizations, and

religious groups. As early as 1956, labor unions,

such as the United Packinghouse Workers and the

United Auto Workers contributed to the MIA and peace

activists such as Homer Jack alerted their

associates to the activities of the MIA. Activists

from southern organizations such as Myles Horton’s

Highlander Folk School and Anne Braden’s Southern

Conference Education Fund were in frequent contact

with King. In addition, his extensive ties to the

National Baptist Convention provided support from

churches all over the nation; and his advisor,

Stanley Levison insured broad support from Jewish

groups.

King’s recognition of the link between segregation

and colonialism resulted in alliances with groups

fighting oppression outside the U.S., especially in

Africa. In March 1957, King traveled to Ghana at the

invitation of Kwame Nkrumah to attend the nation’s

independence ceremony. Shortly after returning from

Ghana King joined the American Committee on Africa

agreeing to serve as vice chair

man of an

International Sponsoring Committee for a day of

protest against South Africa’s apartheid government.

Later at a SCLC sponsored event honoring Kenyan

labor leader Tom Mboya, King further articulated the

connections between the African-American freedom

struggle and those abroad: “We are all caught in an

inescapable network of mutuality” (Papers 5:204).

During 1959 he increased his understanding of

Gandhian ideas during a month-long visit to India

sponsored by the American

Friends Service Committee. With Coretta and

MIA historian Lawrence D. Reddick in tow, King meet

with many Indian leaders, including Prime Minister Jawaharlal

Nehru. Writing after his return, King stated,

“I left India more convinced than ever before that

non-violent resistance is the most potent weapon

available to oppressed people in their struggle for

freedom” (Papers 5:233).

MLK with Malcolm X

Early the

following year he moved his family, which now

included two children,Yolanda and Martin Luther

King, III, to Atlanta in order to be nearer SCLC

headquarters in that city and to become co-pastor,

with his father, of Ebenezer Baptist Church. (The

Kings’ third child, Dexter, was born in 1961; their

fourth, Bernice, was born in 1963.) Soon after

King’s arrival in Atlanta, the southern civil rights

movement gained new impetus from the student-led

lunch counter sit-in movement that spread throughout

the region during 1960. The sit-ins brought into

existence a new protest group, the Student

Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC),

which would often push King toward greater

militancy. King came in contact with students,

especially those from Nashville such as John Lewis,

James Bevel and Diane Nash who had been trained in

nonviolent tactics by James Lawson. In October 1960

King’s arrest during a student-initiated protest in

Atlanta became an issue in the national presidential

campaign when Democratic candidate John F. Kennedy

called Coretta King to express his concern. The

successful efforts of Kennedy supporters to secure

King’s release contributed to the Democratic

candidate’s narrow victory over Republican candidate

Richard Nixon.

King’s

decision to move to Atlanta was partly caused by

SCLC’s lack of success during the late 1950s.

Associate director Ella Baker had complained that

the SCLC’s Crusade for Citizenship suffered from

lack of attention from King. SCLC leaders hoped that

with King now in Atlanta, programming would be

improved. The hiring of Wyatt T. Walker as executive

director in 1960 was also seen as a step toward

bringing efficiency to the organization, while the

addition of Dorothy Cotton and Andrew Young to the

staff infused new leadership after SCLC took over

the administration of the Citizenship Education

program pioneered by Septima Clark. Attorney

Clarence Jones also began to assist King and SCLC

with legal matters and to act as King’s advisor.

As the southern protest movement expanded during the

early 1960s, King was often torn between the

increasingly militant student activists, such as

those who participated in the Freedom

Rides and more cautious national civil rights

leaders. During 1961 and 1962 his tactical

differences with SNCC activists surfaced during a

sustained protest movement in Albany, Georgia. King

was arrested twice during demonstrations organized

by the Albany Movement, but when he left jail and

ultimately left Albany without achieving a victory,

some movement activists began to question his

militancy and his dominant role within the southern

protest movement.

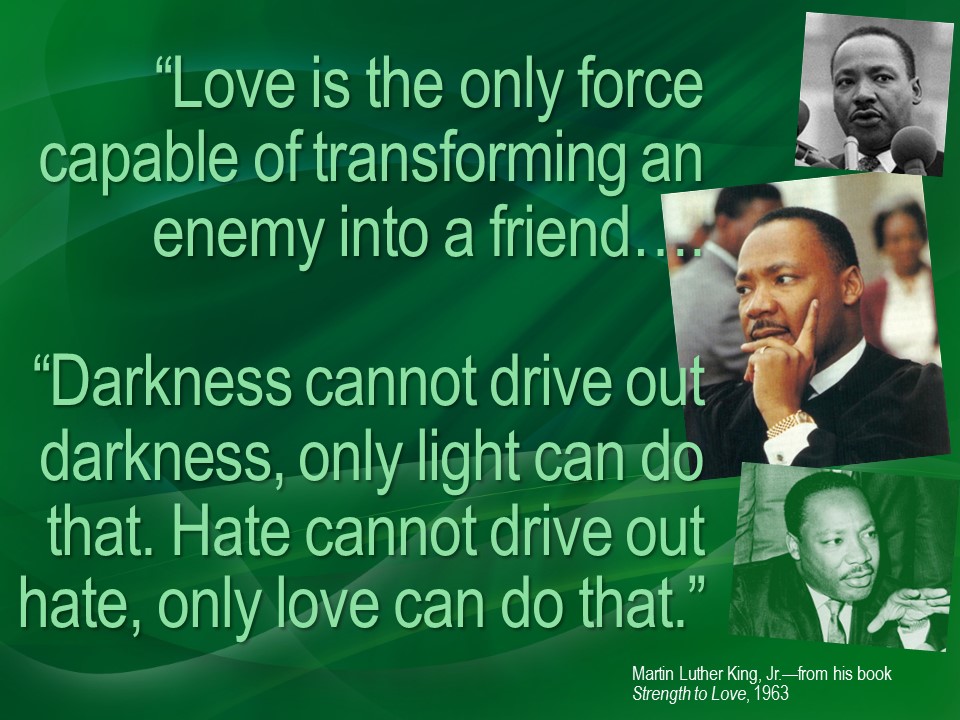

As King encountered increasingly fierce white

opposition, he continued his movement away from

theological abstractions toward more reassuring

conceptions, rooted in African-American religious

culture, of God as a constant source of support. He

later wrote in his book of sermons, Strength to Love

(1963), that the travails of movement leadership

caused him to abandon the notion of God as

“theological and philosophically satisfying” and

caused him to view God as “a living reality that has

been validated in the experiences of everyday life”

(Papers 5:424).

During

1963, however, King reasserted his preeminence

within the African-American freedom struggle through

his leadership of the Birmingham

campaign. Initiated by SCLC and its affiliate,

the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights, the

Birmingham demonstrations were the most massive

civil rights protest that had yet occurred. With the

assistance of Fred Shuttlesworth and other local

black leaders and with little competition from SNCC

and other civil rights groups, SCLC officials were

able to orchestrate the Birmingham protests to

achieve maximum national impact. King’s decision to

intentionally allow himself to be arrested for

leading a demonstration on 12 April prodded the

Kennedy administration to intervene in the

escalating protests. A widely quoted “Letter from

Birmingham Jail” displayed his distinctive ability

to influence public opinion by appropriating ideas

from the Bible, the Constitution, and other

canonical texts. During May, televised pictures of

police using dogs and fire hoses against young

demonstrators generated a national outcry against

white segregationist officials in Birmingham. The

brutality of Birmingham officials and the refusal of

Alabama governor George C. Wallace to allow the

admission of black students at the University of

Alabama prompted President Kennedy to introduce

major civil rights legislation.

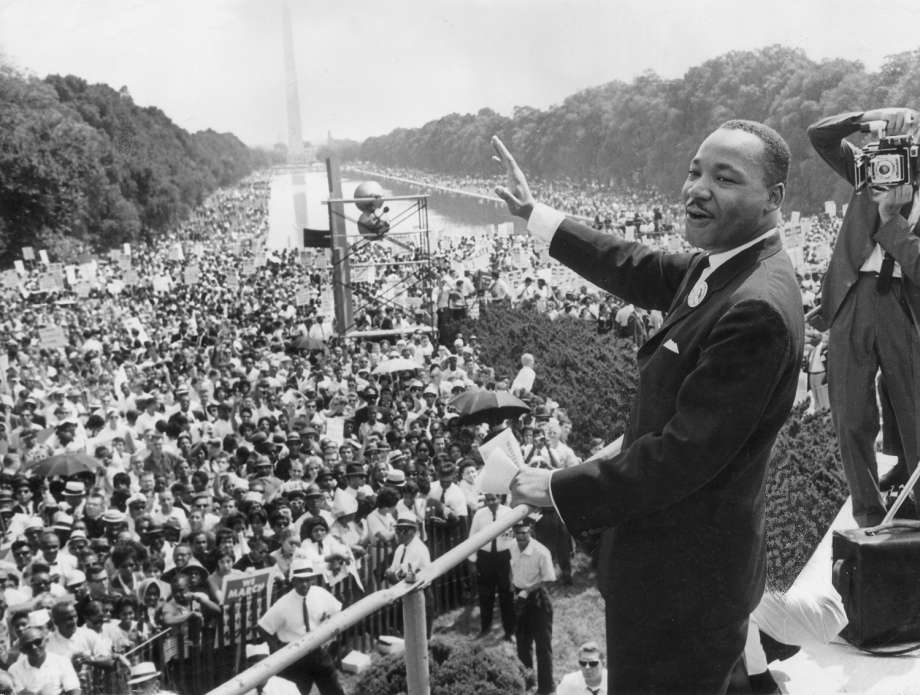

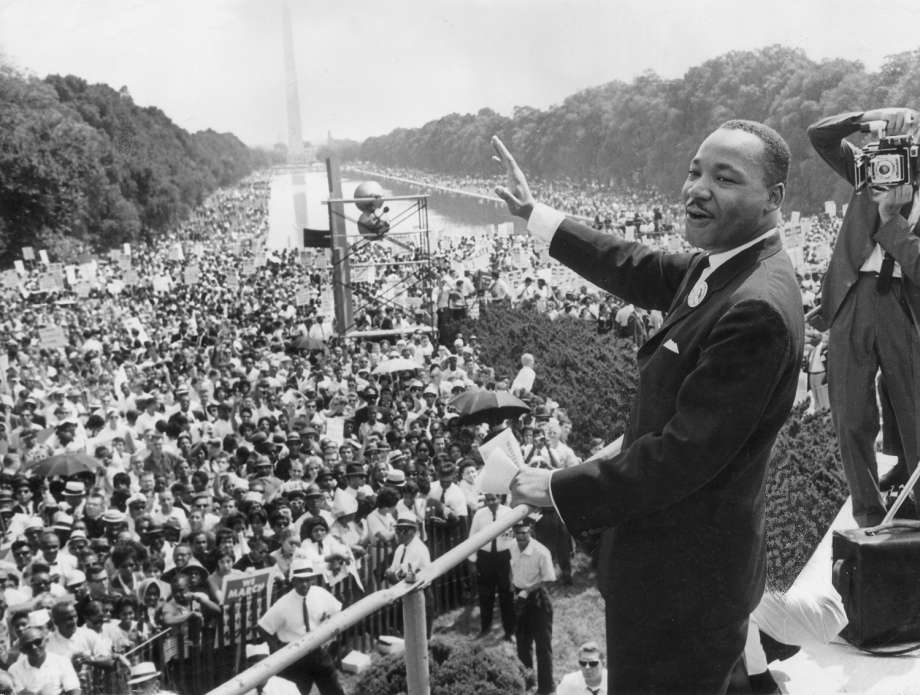

King’s

speech at the 28 August 1963 March

on Washington for Jobs and Freedom attended by

more than 200,000 people, was the culmination of a

wave of civil rights protest activity that extended

even to northern cities. In his prepared remarks

King announced that African Americans wished to cash

the “promissory note” signified in the egalitarian

rhetoric of the Constitution and the Declaration of

Independence. Closing his address with

extemporaneous remarks, he insisted that he had not

lost hope: “I say to you today, my friends, so even

though we face the difficulties of today and

tomorrow, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply

rooted in the American dream . . . that one

day this nation will rise up and live out the true

meaning of its creed:‘we hold these truths to be

self-evident, that all men are created equal.’” He

appropriated the familiar words of “My Country ‘Tis

of Thee” before concluding, “when we allow freedom

ring, when we let it ring from every village and

every hamlet, from every state and every city, we

will be able to speed up that day when all of God’s

children, black men and white men, Jews and

Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to

join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro

spiritual, ‘Free at last, free at last, thank God

Almighty, we are free at last’” (King, Call, 82, 85,

87).

Although there was much elation after the March on

Washington, less than a month later, the movement

was shocked by another act of senseless violence. On

15 September 1963 a dynamite blast killed four young

school girls at Birmingham’s Sixteenth Street

Baptist Church. King delivered the eulogy for three

of the four girls, reflecting, “They say to us that

we must be concerned not merely about who murdered

them, but about the system, the way of life, and the

philosophy which produced the murders” (King, Call,

96).

St. Augustine, Florida became the site of the next

major confrontation of the civil rights movement.

Beginning in 1963 Robert B. Hayling, of the local

NAACP had led sit-ins against segregated businesses.

SCLC was called in to help in May 1964, suffering

the arrest of King and Abernathy. After a few court

victories, SCLC left when a bi-racial committee was

formed; however, local residents continued to suffer

violence.

King’s

ability to focus national attention on orchestrated

confrontations with racist authorities, combined

with his oration at the 1963 March on Washington, made

him the most influential African-American

spokesperson of the first half of the 1960s. Named

Time magazine’s “Man of the Year” at the end of

1963, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in

December 1964. The acclaim King received

strengthened his stature among civil rights leaders

but also prompted Federal Bureau of Investigation

director J. Edgar Hoover to step up his effort to

damage King’s reputation. Hoover, with the approval

of President Kennedy and Attorney General Robert

Kennedy, established phone taps and bugs. Hoover and

many other observers of the southern struggle saw

King as controlling events, but he was actually a

moderating force within an increasingly diverse

black militancy of the mid-1960s. Although he was

not personally involved in Freedom

Summer (1964), he was called upon to attempt

to persuade the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party

delegates to accept a compromise at the Democratic

Party National Convention.

As the African-American struggle expanded from

desegregation protests to mass movements seeking

economic and political gains in the North as well as

the South, King’s active involvement was limited to

a few highly publicized civil rights campaigns, such

as Birmingham and St. Augustine, which secured

popular support for the passage of national civil

rights legislation, particularly the Civil Rights

Act of 1964.

The Alabama protests reached a turning point on 7

March when state police attacked a group of

demonstrators at the start of a march from Selma to

the state capitol in Montgomery. Carrying out

Governor Wallace’s orders, the police used tear gas

and clubs to turn back the marchers after they

crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge on the outskirts of

Selma. Unprepared for the violent confrontation,

King alienated some activists when he decided to

postpone the continuation of the Selma

to Montgomery March until he had received

court approval, but the march, which finally secured

federal court approval, attracted several thousand

civil rights sympathizers, black and white, from all

regions of the nation. On 25 March King addressed

the arriving marchers from the steps of the capitol

in Montgomery. The march and the subsequent killing

of a white participant, Viola Liuzzo, as well as the

earlier murder of James Reeb dramatized the denial

of black voting rights and spurred passage during

the following summer of the Voting

Rights Act of 1965.

After the successful voting rights march in

Alabama, King was unable to garner similar support

for his effort to confront the problems of northern

urban blacks. Early in 1966 he, together with local

activist Al Raby, launched a major campaign against

poverty and other urban problems and moved his

family into an apartment in Chicago’s black ghetto.

As King shifted the focus of his activities to the

North, however, he discovered that the tactics used

in the South were not as effective elsewhere. He

encountered formidable opposition from Mayor Richard

Daley and was unable to mobilize Chicago’s

economically and ideologically diverse black

community. King was stoned by angry whites in the

Chicago suburb of Cicero when he led a march against

racial discrimination in housing. Despite numerous

mass protests, the Chicago Campaign resulted in no

significant gains and undermined King’s reputation

as an effective civil rights leader.

King’s influence was damaged further by the

increasingly caustic tone of black militancy of the

period after 1965. Black radicals increasingly

turned away from the Gandhian precepts of King

toward the Black Nationalism of Malcolm

X, whose posthumously published autobiography

and speeches reached large audiences after his

assassination in February 1965. Unable to influence

the black insurgencies that occurred in many urban

areas, King refused to abandon his firmly rooted

beliefs about racial integration and nonviolence. He

was nevertheless unpersuaded by black nationalist

calls for racial uplift and institutional

development in black communities.

In June 1966, James

Meredith was shot while attempting a “March

against Fear” in Mississippi. King, Floyd

McKissick of the Congress

of Racial Equality and Stokely

Carmichael of SNCC decided to continue his

march. During the march, the activists from SNCC

decided to test a new slogan that they had been

using, Black Power. King objected to the use of the

term, but the media took the opportunity to expose

the disagreements among protestors and publicized

the term.

In his last book, Where Do We Go from

Here: Chaos or Community? (1967), King

dismissed the claim of Black Power advocates “to be

the most revolutionary wing of the social revolution

taking place in the United States,” but he

acknowledged that they responded to a psychological

need among African Americans he had not previously

addressed (King, Where Do We Go, 45-46).

“Psychological freedom, a firm sense of self-esteem,

is the most powerful weapon against the long night

of physical slavery,” King wrote. “The Negro will

only be free when he reaches down to the inner

depths of his own being and signs with the pen and

ink of assertive manhood his own emancipation

proclamation” (King, Call, 184).

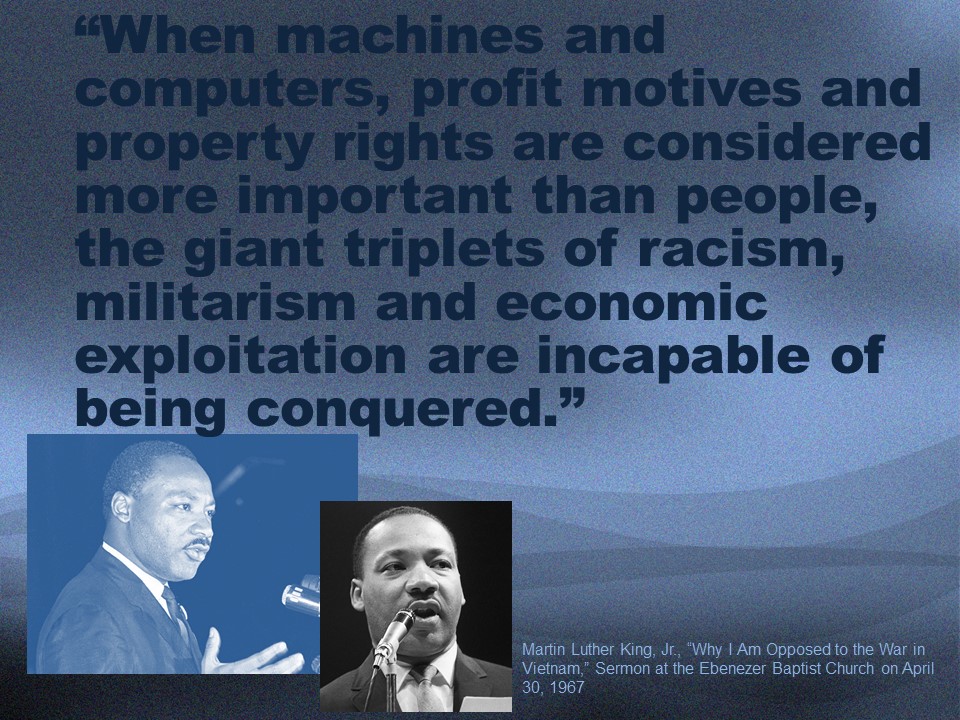

Indeed, even as his popularity declined, King spoke

out strongly against American involvement in the Vietnam

War, making his position public in an address,

“Beyond

Vietnam,” on 4 April 1967 at New York’s

Riverside Church. King’s involvement in the anti-war

movement reduced his ability to influence national

racial policies and made him a target of further FBI

investigations. Nevertheless, he became ever more

insistent that his version of Gandhian nonviolence

and social gospel Christianity was the most

appropriate response to the problems of black

Americans.

In December 1967 King announced the formation of the

Poor

People’s Campaign, designed to prod the

federal government to strengthen its antipoverty

efforts. King and other SCLC workers began to

recruit poor people and antipoverty activists to

come to Washington, D.C., to lobby on behalf of

improved antipoverty programs. This effort was in

its early stages when King became involved in the Memphis

sanitation workers’ strike in Tennessee. On 28

March 1968, as King led thousands of sanitation

workers and sympathizers on a march through downtown

Memphis, black youngsters began throwing rocks and

looting stores. This outbreak of violence led to

extensive press criticisms of King’s entire

antipoverty strategy. King returned to Memphis for

the last time in early April. Addressing an audience

at Bishop Charles J. Mason Temple on 3 April, King

affirmed his optimism despite the “difficult days”

that lay ahead. “But it really doesn’t matter with

me now,” he declared, “because I’ve been to the

mountaintop [and] I’ve seen the Promised Land.” He

continued, “I may not get there with you. But I want

you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get

to the Promised Land.” (King, Call, 222-223). The

following evening the assassination

of Martin Luther King, Jr. took place as he

stood on a balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis.

A white segregationist, James Earl Ray, was later

convicted of the crime. The Poor People’s Campaign

continued for a few months after his death under the

direction of Ralph Abernathy, the new SCLC

president, but it did not achieve its objectives.

Until his

death King remained steadfast in his commitment to

the radical transformation of American society

through nonviolent activism. In his posthumously

published essay, “A Testament of Hope” (1969), he

urged African Americans to refrain from violence but

also warned, “White America must recognize that

justice for black people cannot be achieved without

radical changes in the structure of our society.”

The “black revolution” was more than a civil rights

movement, he insisted. “It is forcing America to

face all its interrelated flaws-racism, poverty,

militarism and materialism” (King, “Testament,”

194).

After her husband’s death, Coretta Scott King

established the Atlanta-based Martin Luther King,

Jr., Center for Nonviolent Social Change (also known

as the King

Center) to promote Gandhian-Kingian concepts

of nonviolent struggle. She also led the successful

effort to honor her husband with a federally

mandated King national holiday, which was first

celebrated in 1986.

Sources:

Introduction, in Papers 1:1-57.

King, “An Autobiography of Religious Development,”

12 September-22 November 1950, in Papers 1:359-363.

—, “Eulogy for the Young Victims of the Sixteenth

Street Baptist Church Bombing,” in A Call to

Conscience, eds. Clayborne Carson and Kris Shepard,

New York: Warner Books, 2001, pp. 95-99.

—, “I Have a Dream,” in A Call to Conscience, eds.

Clayborne Carson and Kris Shepard, New York: Warner

Books, 2001, pp. 81-87.

—, “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop,” in A Call to

Conscience, eds. Clayborne Carson and Kris Shepard,

New York: Warner Books, 2001, pp. 207-223.

—, “Kick Up Dust,” Letter to the Editor, Atlanta

Constitution, in Papers 1:121.

—, “My

Trip to the Land of Gandhi,” in Papers 5:231-238.

—, “Pilgrimage to Nonviolence,” in Papers 5:419-425.

—, Remarks Delivered at Africa Freedom Dinner at

Atlanta University, in Papers 5:203-204.

—, Strength to Love, 1963.

—, “A Testament of Hope,” in Playboy, 16 January

1969, pp. 193-194, 231-236.

—, “Where Do We Go From Here?” in A Call to

Conscience, eds. Clayborne Carson and Kris Shepard,

New York: Warner Books, 2001, pp. 171-199.

—, Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community?,

Boston: Beacon Press, 1967.

SOURCE OF THE

TEXT OF THIS BIOGRAPHY:

http://kingencyclopedia.stanford.edu/encyclopedia/encyclopedia/enc_martin_luther_king_jr_biography/index.html

ALL IMAGES are

copyrighted by their respective owners.

|